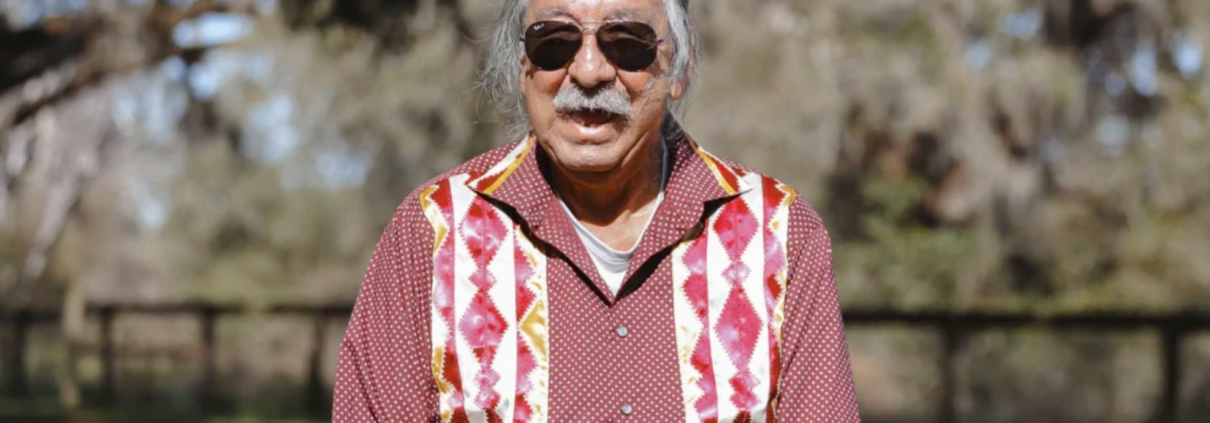

Welcome home, Leonard

In one of the last acts of his presidency, President Biden freed Leonard Peltier — a member of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians and the longest serving Native political prisoner in U.S. history. And today, February 18, 2025, Leonard was was released from federal prison.This is thanks in no small part to our collective activism, sending hundreds of thousands of messages to the White House urging the president to act on behalf of freedom and justice. With your help, NOA was able to send 135,491 letters asking for Leonard’s freedom and gather 142,184 petition signatures. Our hearts are full for Leonard Peltier, his family, and all of Indian Country as he is finally granted freedom after nearly 50 years behind bars.

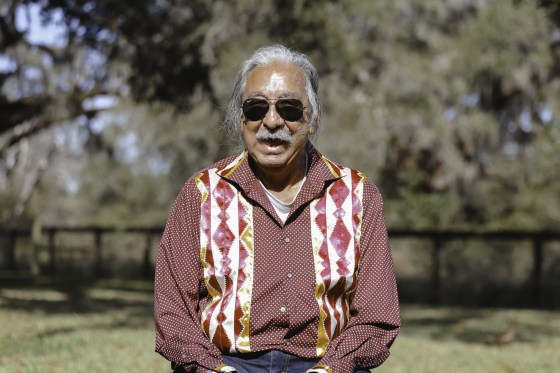

photo by Angel White Eyes / NDN Collective

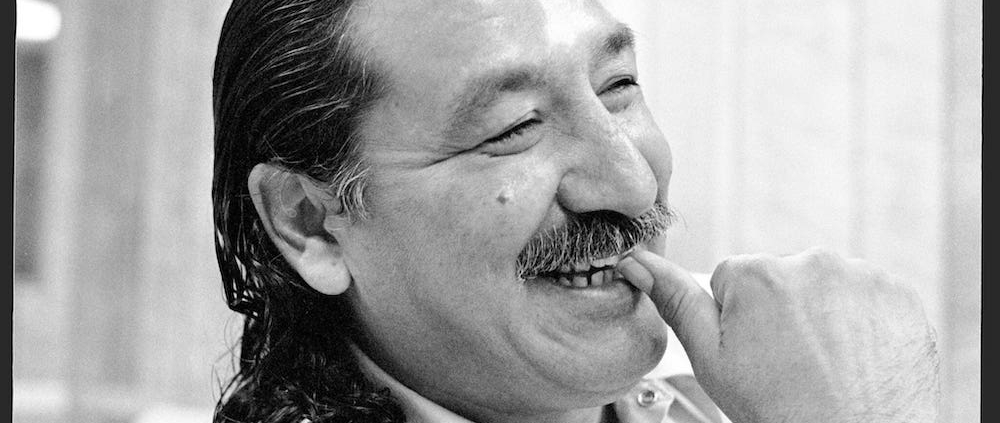

Leonard’s incarceration came to symbolize the injustices Native peoples face in defending our lands and civil and inherent rights. His resilience has stood as a testament to the enduring strength of Native peoples in the face of systemic racism and oppression. Throughout his incarceration, Leonard remained unwavering in his commitment to defending Indigenous rights. He has inspired activists worldwide to stand up to governments and systems that marginalize people of color.

His lifelong advocacy for Native rights and justice will continue encouraging Indigenous activists for generations. Today, we celebrate not just Leonard’s long overdue freedom, but an Indigenous movement he helped create.

Over the past nearly 50 years, international leaders including Pope Francis, Saint Mother Teresa, Nelson Mandela, the Dalai Lama, and Coretta Scott King have called for Leonard Peltier’s release.

Our activism, alongside generations of leaders, led seven U.S. senators and 26 representatives to sign a letter late last year urging President Biden to grant clemency. And our calls for action led to this moment.