Trump Rolls Back Biden Order Strengthening Tribal Sovereignty

Move is “a huge setback for federal-tribal relations”

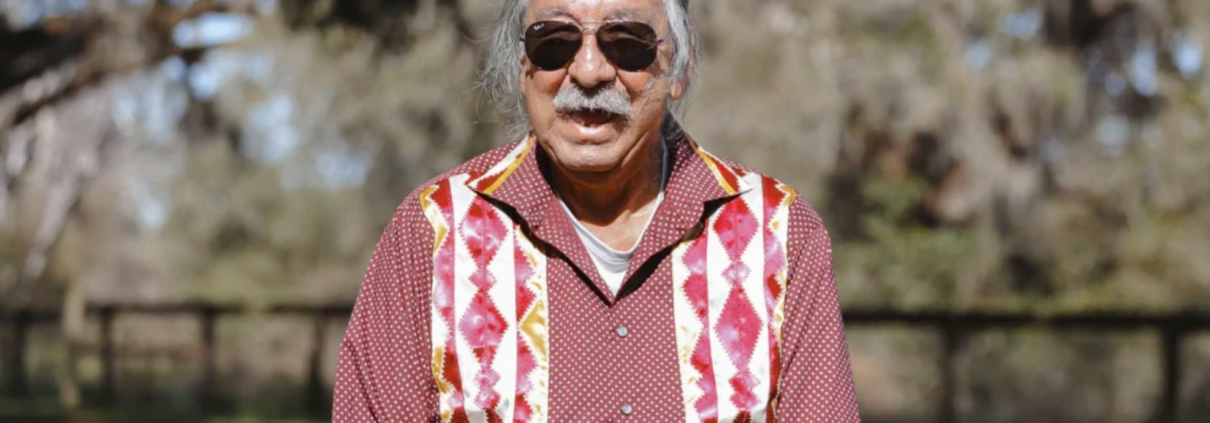

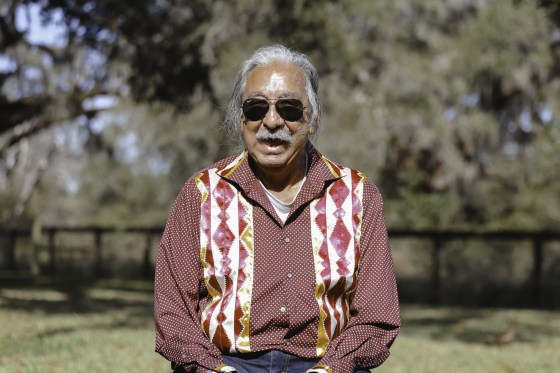

New York, NY — President Trump revoked an executive order signed by former President Joe Biden directing federal agencies to strengthen tribal sovereignty and address how the agencies carry out their duty to consult with Tribal nations. The following statement from Judith LeBlanc (Caddo), executive director of Native Organizers Alliance and NOA Action Fund, can be quoted in part or in full.

“The actions by the Trump administration to roll back an order to strengthen Tribal sovereignty, that hundreds of Tribal nations and tens of thousands of Americans called for, is a direct attack on our sovereignty and a huge setback for federal-tribal relations.

President Biden issued this executive order in response to demands by sovereign nations, Native organizations, and thousands of Americans, to do more to protect and uphold Tribal sovereignty. For too long, federal agencies have done too little or nothing at all in their essential role of consulting and engaging with Tribes. As sovereign nations, Tribes have the right to determine how lands are used and developed but too often the federal agencies charged with consulting with Tribes about their ancestral homelands did the bare minimum, or nothing at all, to ensure that tribes had a say in the future of their lands and people. This is in violation of the inherent and constitutional rights of tribes to make decisions about their lands and the well-being of tribal members.

In recent years, there has been significant progress in strengthening the federal-tribal relationship. In rolling back this order, President Trump is not only acting in opposition to the will of tens of thousands of Americans, he is setting back the significant progress that has been made in strengthening Tribal sovereignty.

While the Trump administration may have decided against the will of the American people by rolling back this executive order, it is critical to note that this does not change the fact that the Trump administration and all federal agencies are still required to consult with and engage Tribes on matters that impact Tribal members and Tribal lands and resources. That has not changed, and neither has the Constitution.

Indian Country will be watching to ensure that the rights of sovereign nations are upheld and sovereignty is respected.”

###

Contact:

Ruby Stacey, Pyramid Communications

rstacey@pyramidcommunications.com

360.565.6956 cell

NDN Collective

NDN Collective