Welcome to Interviews for Resistance. In this series we’ll be talking with organizers, troublemakers and thinkers who are working both to challenge the Trump administration and the circumstances that created it. It can be easy to despair, to feel like trends toward inequality are impossible to stop, to give in to fear over increased racist, sexist and xenophobic violence. But around the country, people are doing the hard work of fighting back and coming together to plan for what comes next. This series will introduce you to some of them.

Audio of the interview:

Judith LeBlanc: My name is Judith LeBlanc. I am a matter of the Caddo Nation of Oklahoma. I am the director of the Native Organizers Alliance.

Sarah Jaffe: What is going on at Standing Rock?

Judith: Standing Rock is everywhere right now. [Thursday, February 2] there was a march in downtown Seattle, hundreds of people in support of the Seattle City government resolution to divest from Wells Fargo.

Standing Rock is everywhere and it is a beautiful thing because water gives us life and water has become, because of what has happened at Standing Rock, a symbol for all that is sacred and important for humanity and for Mother Earth. We have an organized approach to moving the battle for Standing Rock to the other reservations of the Oceti Sakowin and to spread the organizing all across the country, because tens of thousands of people have gone through the Oceti Sakowin camp and have become a part of this magic moment in Indian country. The Oceti Sakowin elders who came together for the first time since the Battle of the Little Bighorn, extinguished the fire that had been burning to guide the prayers of the camp, to guide the way the camp existed. They now are planning to visit each of the territories of the Oceti Sakowin to fortify the resistance to potential takeovers of our land and the infringement on our sovereignty.

Every social movement going into new stages is never smooth or even. In the last few days some of those in the camp who want to remain in the area built another camp outside of the Oceti Sakowin camp a little ways down the road. There were many people arrested as a result.

One of the difficulties that we face in Indian Country is that the pipeline for the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe is one major issue, but there are other many, many major issues that the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe is working on all at once. The median income at the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation is a little over $13,000. There are key issues of healthcare and economic development and education. In many ways, I think the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe has really been showing how difficult and how important it is to build unity in support of protecting our larger rights, Indian Country-wide right to protect our sovereignty and that is what the fight in stopping the pipeline was about. Because when the Bismarck folks said, “No,” to the pipeline, their “No” stuck. When the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe said, “No,” the Energy Transfer Partners said, “Well, anyway…” and acted as if they could build this pipeline.

We have run up against a very difficult situation with the Trump administration being elected to office. One of the senators from North Dakota, very pro-pipeline, has become the head of the Chair of the Indian Affairs Committee in the Senate. We are up against a situation where it is very hard to see how the pipeline will be stopped, unless we continue to put the pressure where it needs to be, on the 17 banks that have invested, continue to pressure the Trump administration to not violate the law and proceed with the environmental impact study that was mandated under the Obama administration. It is a tough fight in the next days ahead. It will be determined by whether or not the government violates the will of the people who have been in solidarity with Standing Rock and the 17,000,000 people along the shores of the river.

Sarah: What has it been like this winter? There have been people camped out all the way through, right?

Judith: I like to think about Standing Rock, what it was like on the ground there September 1st when it was warm. I think about it at sunset. It was a very golden kind of light where thousands of Indian people had gathered in solidarity. We created a 21st century Indian city. We had our own kitchen serving three hot meals a day, coffee all day long, and a school and a radio station, and the feeling of prayers and people power being the most amazing medicine that our people could experience because of all of the trauma, all of the deep generational problems that come with the policies of the U.S. government since colonial times.

People began to prepare in October for the winter, because North Dakota winters, you don’t play with them. Very, very severe. Collectively, people began to prepare for winter starting in October and early November, fortifying the different places where people were sleeping, yurts, insulating the teepees, redistributing the kitchen so that it could be in different sectors of the camp. But as we moved into December, when the big blizzard hit, it became clear that peoples’ lives were in danger. There was a call for people to protect themselves by taking the struggle home, to go home and to continue to support the legal fight.

Many, many people followed that directive, because it is just too tough. Others stayed and really have dug in and therefore the dismantling of the camp right now is a complicated business. We have to use backhoes and teams to remove the structures that were set up because it is on a flood plain. The floods are going to be very, very bad this year because of the amount of snow. There is great danger for the people who are camped there. Back in the day, when our people were there without down, without wool socks, it is really hard to imagine how amazing our people were to be able to not only survive, but to continue to thrive and grow as a people under such severe weather conditions.

Sarah: Trump and his people have already made noises about trying to sell off more native peoples’ lands. How can people respond to that if they are just going to try to privatize everything?

Judith: It goes to the heart of how the vast majority of people in this country is going to protect hard-won rights and programs and continue to push forward for the things our communities need. Sovereignty is the bottom line. In Indian Country, we are preparing now for a mobilization to Washington. The time is now to plant all of our nations’ flags in [Washington] D.C. to signal to both the Trump administration and Congress that we are here to stay in this country as sovereign nations, that we are ready to fight for sovereignty.

We are nations that have not only a legal, but a moral, responsibility to protect our land, our air, our water for all of humanity. Sovereignty is also a way to protect the communities and the states and the rivers that affect all of us. When you have tribal governments that are able to do what is best for Mother Earth, then it benefits the border communities, it benefits the economy of states, and it makes our country a better place to live for all and will save the planet. At this point, the Trump administration signaled, even before taking office, that they were willing to follow a policy of privatizing Indian land for oil, for energy resources.

The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe is calling on people, all people, Indians and non-Indians to come to D.C. March 6-10th where we will establish a prayer camp on the National Mall and we will spend our days doing actions, flooding Capitol Hill, and then, marching on the White House on March 10th. We are working to bring together the other 300 tribes that stood with Standing Rock. Over 300 tribes, many of them derive significant revenue streams from fossil fuels, but they stood with Standing Rock because it is a matter of tribal sovereignty. We have the right to decide for our land, our water, and air, how our people are affected by these greedy corporations who will stop at nothing to maximize their profits.

When you look at the Navajo Reservation, you look at the reservations in Nevada, all over the country fossil fuel corporations have come onto our land, paid us money, taken their profits and run, leaving generations of disease and death in their wake. We are inviting all of these tribes to march on the White House to say, “President Trump, you meet with us, you deal with us as sovereign nations.” The Indian people who come from all over the country, as we did flock to Standing Rock Reservation, we will flock to Capitol Hill and lay it on the line with the members of Congress.

In this session of Congress, there are many issues that affect our sovereignty: the attack on Obamacare is an attack on the right to healthcare for Indian people. Legally, we have been guaranteed, from birth to death, quality healthcare and we have not been able to achieve that. If Obamacare is destroyed, it will destroy some steps forward that we took under the Indian Health Improvement Act, which was incorporated into Obamacare. We are going to make a statement, just as the people did at the airports on protecting the rights of immigrants and as we did during the Women’s March. President Trump, we are on our way.

Sarah: There was another trip during the Keystone XL fight, where there was also a prayer camp set up in D.C. Correct?

Judith: Correct. Many of the veterans that organized those events and orchestrated that victory to stop the pipeline are the lead on this, like Faith Spotted Eagle from Yankton tribe who received one Presidential electoral vote here in the state of Washington, the Indigenous Environmental Network. Many of the grassroots leaders, many of them who were the headsmen and some of the spiritual leaders at the Oceti Sakowin camp are in the lead of this initiative.

The challenge now is: How do we not only continue to mobilize our people and build strong alliances with non-native, environmental, faith-based groups, the labor movement, but also how we support at the grassroots an organized strategic role that people can play in fighting for the everyday immediate policies that are being debated and need the support of a movement for them to become transformational policies, even under a time when the right wing is on the offensive? That is a big challenge for us in Indian Country, how we will continue to organize, not just mobilize.

Sarah: Let’s talk a little bit more about the role of these divestment campaigns targeting the banks and the financial institutions that are funding the pipeline and how they connect to things like Wall Street deregulation that Trump has called for.

Judith: This is a very important strategy in order to get at the systemic nature of the role that fossil fuels play in the economy and in creating the huge threat to the existence of our planet. If you want to go to the roots, the economic and structural roots of a problem, you have to dig into the role of financialization and the banks. This divestment movement has given a handle for many who wouldn’t come to Oceti Sakowin camp, who need to do work in their own communities to make the links between the problems we face and the role that banks and the economic system plays in the broader crisis.

You look back over many decades, during the anti-apartheid movement and the global solidarity movement, divestment was a key tool. In other countries, there is incredible mobilization that has resulted in some of the banks in other countries divesting from Energy Transfer Partners. The divestment strategy has also been a way for us in this moment to build global awareness of the threats that exist to the existence of our planet.

No matter how strong capitalism seems to be, it is inherently full of contradictions and therefore masses of people, when organized, even if not the majority, can have an impact. We have organized this alliance, joined a coalition that involved many, many groups—faith groups, as well as divestment groups and environmental groups like 350.org—in doing a serious of actions in the last few days to pressure the 17 banks who are invested in Energy Transfer Partners to meet with the tribe. To divest, but to do so on the basis of meeting with the tribes and understanding what the issues are and the impact the pipeline can have. We have also had tremendous numbers of people, I can’t remember the figures of people who closed their personal accounts that were in some of the 17 banks. It has given many people the ability to say, “Amen,” in their personal lives, to live a life that is actually in sync with their beliefs that we all have a role to play in saving Mother Earth.

I think the divestment strategy and the pressure that it is putting on Energy Transfer Partners is very important in shifting those around the Trump administration to think about the bottom line. At this point, the pipeline is losing money. It is not a good business investment. Energy Transfer Partners acted for the last two years in the business pages in North Dakota and the Wall Street Journal that “Hey, we have got this. We have the permit. This is going through.” They kept building the pipeline until it got to the point where it was so close to the reservation’s water supply that the resistance began. I don’t think they anticipated the resistance would last as long as it has and I think it has begun to dawn on some of the investors, especially the banks outside of the country, that even if the pipeline was moved away from the current path, that the resistance would continue. It wasn’t the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe saying, “Not in my backyard.” They were saying, “Not in anyone’s backyard.” Pipelines break.

It is a classic capitalist situation. They overproduce vehicles and ways that oil should be transferred. Truth is, they don’t need this pipeline. It is not a necessity. We are hoping to convince the banks and therefore the people of Wall Street who have some semblance of business sense to pull out of this.

Now, the Trump administration, we are dealing with one that is not rational. Even the Koch brothers are questioning the direction of what the Trump administration is going on, which is a direction of chaos. Shooting from the hip and asking questions later. I think the divestment strategy is even more important, because there are some sectors of finance capital, some sectors of corporate America who are rational and if you create more chaos, it is not good for business. If there is no stability, markets respond. The divestment strategy is a good strategy because you are pointing people to the root causes in the capitalist system, but in this moment it can have a huge impact on Wall Street and therefore a mitigating factor on the Trump administration’s chaotic cowboy attitude.

Sarah: You spent a lot of time working with United for Peace and Justice (UFPJ), the big umbrella movement against the wars during the Bush years. Now that we are, again, in a moment with a right-wing president who looks like he might start a war any day now, can you talk about some lessons from that movement?

Judith: I have thought a lot about this in the last two weeks. I had the honor of speaking at the Women’s March in D.C. I was standing on the stage and I was looking out at the people and I thought about what it was like when United for Peace and Justice brought together over 1,000 organizations; national immigrant rights, labor, faith-based peace groups, a real cross section of movements and organizations. We did demonstrations of hundreds of thousands for years to put the pressure on the Bush administration and to open up the political space to connect the policies of militarism and war with the economic and the moral impact in our communities. The economic impact was clear, that more money was being and continues to be spent on the Pentagon and wars than on the social safety net that is needed in our communities.

I think the Iraq anti-war movement had a huge impact on changing public opinion. Some say, “Well, you didn’t stop the war,” but we did gain political momentum that became the driving force behind people pushing for the election of a president who had committed to a date certain for troop withdrawal from Iraq.

But, the truth is, that we were so busy mobilizing against the full spectrum of the Bush agenda that we did not pay enough attention to organizing. We focused on trying to build unity across sectors and to maintain a coalition effort that was focused on ending the war, but did not pay enough attention to how grassroots folks continue to be engaged in between mobilizations. I think it was because of the nature of the urgency of the moment and the nature of the wars that were going on in Afghanistan and Iraq. But, I also think it was because the movement, as a whole, had that blind spot that grassroots organizing was not the key element of work in communities. Although there has always been a sector of people, economic and racial justice organizations, that have been doing that. We weren’t able to incorporate it as a part of that movement-building project.

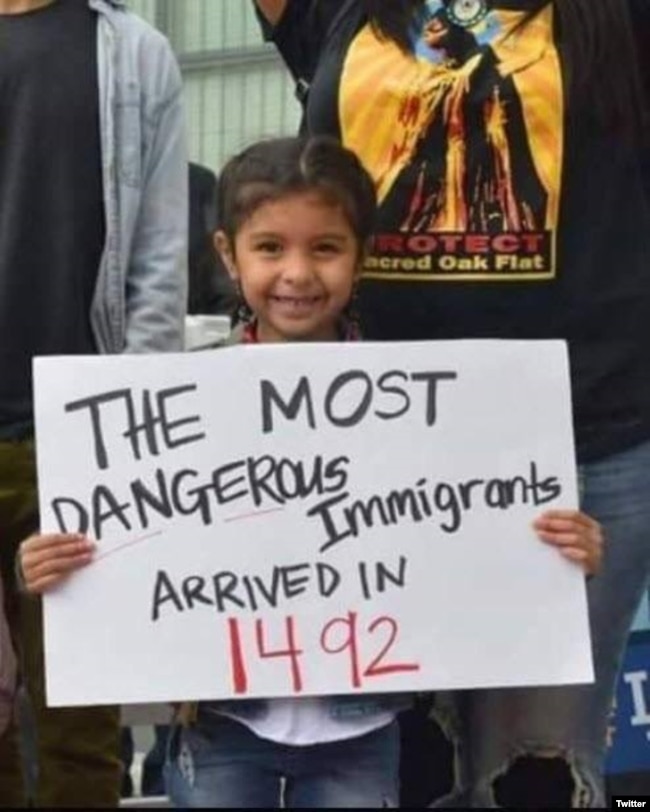

We are in a totally different place now. In fact, the first two weeks of the Trump administration have shown that we are at a level where not only are people willing to mobilize, but people are making the connections from their own self-interest to people way beyond their own immediate communities. That is what was powerful about the Women’s March and the demonstrations at the airports. Number one, it was grassroots-driven. When you looked at the signs at the marches all over the country, but especially in Washington, the handmade signs that people brought with them were about democracy. That the protection of women’s rights was part and parcel of protecting the system of democracy in its best and truest form. When you look at the airport demonstrations, people said, “I have to be there to support and stand on the side of people who are being detained at the airports.” I think it is because of the incredible grassroots organizing and work that has been done during the eight years during the Obama administration.

We had a period where people began to go deeper into what it takes to change the economic system. There has been more experimentation and initiatives around generating sustainable green economic development. There have been unlikely coalition relationships around an array of issues. There’s a broader cross section of groups and infrastructure out there that is willing to support this grassroots upsurge by delving deeper into political education and helping people to develop themes that will sustain them, that we need to push back the attacks that we are facing.

There is an array of issues that people are ready to promote and develop a sustained, strategic campaign on. That wasn’t the case when Bush was elected. We were just in full hair on fire, “We have got to show our power in the streets,” mode. It is the same now, but the difference is that I think people are ready to dig in for the long haul. We are not going to solve this with one demonstration. We are not going to solve this simply with anger. We have to use all the tools in our toolbox, from divestment strategies to deep political education that helps people understand the roots of the problems and not just respond to the agitation and chaos. And we need to be organized. This is going to take years to deal with and you can’t burn yourself out. We are in a marathon, not a sprint.

I think the Standing Rock moment has laid the basis for people to understand that we need organizing at the community level that is led with love and open hearts and led by values. That we are not on the defensive. We are on the offensive. We understand that we have to reach out to people who maybe didn’t vote and those who maybe voted for Trump, because there already is the beginnings of buyer’s remorse. People were swayed by the values-led campaign that Trump did and now we need to organize and lead with movements that are value-centered, that are rooted in love of humanity.

That is what you saw at the airports. That was a beautiful thing. My heart soared like an eagle to understand that even through hate and the racist agitation that has become the norm in political discourse, that many white people understood that they have a personal stake and responsibility to stand on the side of Muslims and people of color who were being attacked and detained. That solidarity is the norm, not the exception.

UFPJ, our mission was to try to build that unity. When it was working well, it was a beautiful thing. We need that kind of level of collaboration, and we also need to do the work at the grassroots that taps into the values that people share, the long-term work of going deep into people’s hearts and minds.

The Native people, we have a special role to play. Our culture, our experiences for many people are a source of inspiration. No matter what the impact of the initial colonization was, no matter all of the attempts to sideline and to erase us from this country, we not only have survived, but we have thrived.

Sarah: How can people keep up with you?

Judith: Native Organizers Alliance is putting together a very broad cohort of native trainers that can support tribes and native non-profits and social movement activists at the local level. We are going to be working with Oceti Sakowin elders in South Dakota to Missouri to protect the water and to empower tribal governments to lead the water protection that needs to happen, when the EPA could be gutted. We are also working with organizers on the Navajo Reservation to develop a Colorado River protection project which would involve all of the states along the Colorado River, starting with the tribes and the activists who have been working for generations on the uranium contamination of the water there and land.

We are also conducting our annual National Native Community Organizing Training in August, which is a six-day training. We have done it for six years. Hundreds of people have come through the training and many of our alumni were playing important roles at the Oceti Sakowin camps. Our curriculum is rooted in our inter-tribal cultures. Community organizing is not an idea that a few white guys in Chicago came up with. It is as old as dirt. Our communities have always been premised on the idea of collective economies, collective resolutions to problems. We are using our history and experiences to develop curriculums that build and strengthen those traditions.

We are also collaborating on an array of voter protection and civil rights issues, because Indian Country had the largest number of Indian candidates in U.S. history ran in 2015. We have an array of elected officials in states that are controlled by the right wing. We will be doing a lot of work to help them develop an inside/outside strategy.

Interviews for Resistance is a project of Sarah Jaffe, with assistance from Laura Feuillebois and support from the Nation Institute. It is also available as a podcast.

Originally appeared on InTheseTimes.com