Many Native Americans, Citing History, Angry Over Trump Immigration Policy

WASHINGTON — “Indian Country remembers,” Mark Trahant, editor of Indian Country Today wrote in Monday’s edition of the pan-Native news site. “This is not the first administration to order the forced separation of families.”

He later told VOA, “I basically wanted to show the recurring nature of history. It’s a story so familiar.”

President Donald Trump’s “zero tolerance” immigration policy has separated nearly 2,000 youths from their parents since April, triggering outcry from many Native Americans who find parallels in their own history with the U.S. government.

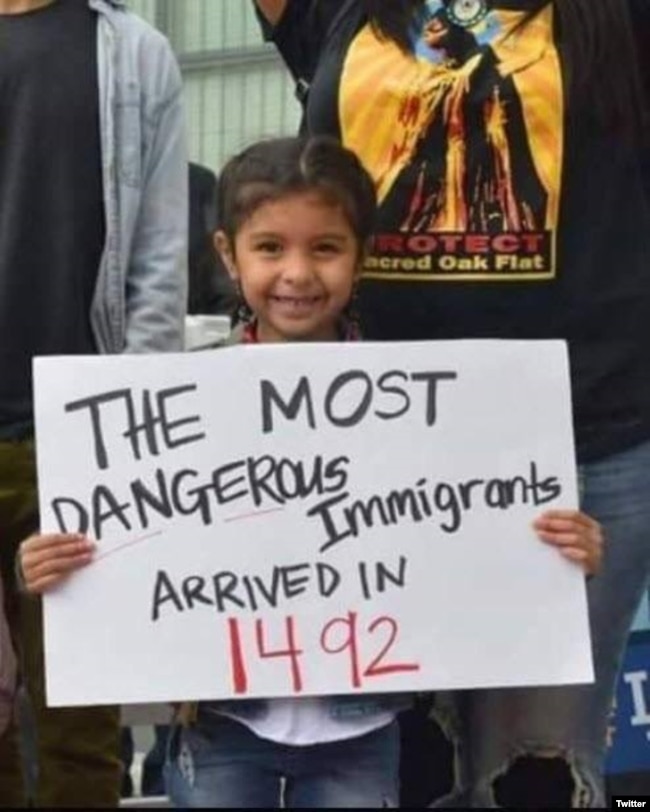

Author, speaker and storyteller Gyasi Ross, who comes from the Blackfeet Nation and how lives on the Port Madison Indian Reservation near Seattle, Washington, suggested on Twitter that the policy is no surprise:

White liberal friends stop saying that separating children from their parents is “unAmerican.” That is ahistorical & insensitive as hell to the 100ks of Native people who were separated from their children by official US policy from boarding schools & the Indian Adoption Project.— (@BigIndianGyasi) June 16, 2018

Native Americans are no strangers to the break-up of families.

“Most [non-Native] Americans do not know their own history, partly because any history that was embarrassing was not taught in school,” said Oglala Lakota journalist Tim Giago, editor of Native Sun News Today. “Native Americans were taken from their parents starting in the late 1800s and shipped to places like Carlisle, PA and Genoa, Neb. to Indian boarding schools. We are still suffering from the trauma it caused.

Fellow journalist Vi Waln, editor of the Lakota Times, expressed a sense of solidarity with those detained by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

“Many Indigenous people are praying for the [detained undocumented] children to be reunited with their families and for the United States to do the right thing,” Waln said. “But we know from experience that this might not happen.”

O.J. Semans, a Rosebud Sioux tribe member and executive director of South Dakota-based voting-rights group Four Directions, echoed Waln’s comment, remembering another government policy which encouraged placement of Native American children in non-Native foster families.

“In the 1970s, we had 25 to 35 percent of tribal children ripped away from their families. It took until 1978 to get Congress to create a law, the Indian Child Welfare Act, to curtail the abductions,” he said, predicting that the current policy of separating migrant and refugee children from their parents will leave lasting scars.

“The trauma of children being ripped away from their parents — the only true love they have — will haunt their dreams and memories till the day they die,” Semans said.

One Native American mother offered heartfelt sympathy for the immigrant parents.

“I just can’t imagine my children being taken away and not knowing if I will ever see them again,” said a member of the Kickapoo Tribe in Kansas, who asked that her name not be used.

She said she believes the policy is racist: “Do you think we’ll see this happening to Canadians illegally crossing the border? No!”

Jefferson Keel, president of the National Congress of American Indians, released a statement Tuesday which said, in part, “Congress and the President should take heed of such abhorrent mistakes from the past and actually live the moral values this country proclaims to embody by immediately ending this policy and reuniting the affected children with their parents. Families belong together.”

But not all Native Americans oppose Trump’s policy.

“I think we as a government have the right to detain anyone who comes here illegally,” said Rick Cuevas, a disenrolled member of the Pechanga Band of Luiseño Mission Indians in California and author of the Original Pechanga blog.

“And those who are going after the Trump administration now were the same ones protecting Barack Obama as he was separating children from parents. His policies allowed 50,000 unaccompanied minors into the country,” he added.

A surge in migration of unaccompanied minors in 2014 led the Obama Administration to place unaccompanied minors in closed housing units until they could be transferred to family in the United States while they awaited court proceedings.

Trump has blamed Democrats for the current policy, announced in April, citing a “horrible” laws that call for children of families attempting to illegally cross the U.S. border to be taken from their parents.

However, there is no U.S. law or court decision that mandates that action.

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) says it has no policy on separation, but that children and parents may be separated in situations in which “DHS cannot ascertain the parental relationship, when DHS determines that a child may be at risk with the presumed parent or legal guardian, or if a parent or legal guardian is referred for criminal prosecution, including for illegal entry.”

In 2017, U.S. border agents apprehended more than 41,000 unaccompanied minors attempting to cross the southwest border of the U.S., and U.S. customs officials report that between October 2017 to March 31, 2018, nearly 40,000 families attempted the same crossing.

Reprinted from Voice of America News